The teenager who drew edible maps for Australia’s wartime pilots

Kevin Bovill contributed this article.

At 18, Cecily Sandercock found herself on a high stool in front of a drawing desk in the office of the United States Army Services of Supply in Victoria Park, Queensland.

“The drawers in my desk contained all kinds of pens and drafting shapes including several I had never seen nor handled before,” she wrote in her journal.

It was October 1943, four years after the start of the second world war, and a young Sandercock “wanted to do something useful for my country, but what could it be?”

In a new collection donated to the Queensland State Library by Sandercock’s family, the Australian woman’s wartime work as a cartographer in the US army is intricately documented through memorabilia, enriching our understanding of women’s contributions to the war.

‘We had to swear that we would not reveal anything’

Sandercock left school at 17, then studied at a technical art school, and had begun work in a photography studio where she retouched photos, mainly of young men going off to war to give to parents and partners.

“For her, that was incredibly boring,” her daughter, Anna Fearnley, says.

“So, she went to the army.”

The US army had begun moving large numbers of troops to Australia at the end of 1941 as Japanese forces advanced through south-east Asia, and in July 1942 transferred its headquarters from Melbourne to Brisbane, where jobs became available for civilians. There, Sandercock went for a position as a tracer.

Sandercock’s father, Cecil, was a draughtsman who had taught her map-drawing. After her time in art school “she had a portfolio ready to go” and “got the job that day”, Fearnley says.

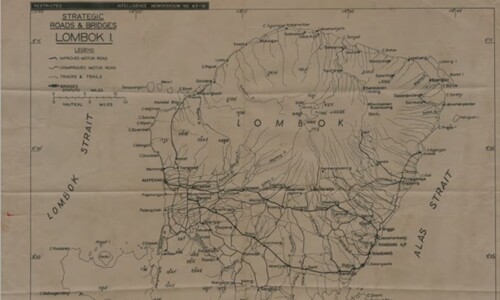

As a tracer, Sandercock made rough drawings of site plans, camps and roads. One map preserved in the library’s collection is of the Indonesian island of Lombok, produced from a mixture of a draftsman’s first rough work and aerial photography, which Sandercock would have consulted. In this unit, she worked alongside a number of other Australian women and men.

She was then invited to do topographical work in graves registration. “Perhaps [the captain] had noticed how much I enjoyed poring over maps, that I should be the one to be asked,” Sandercock wrote in her journal. “Naturally I answered yes.”

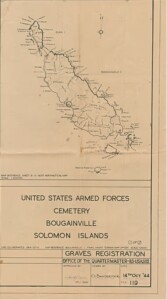

In this unit, she plotted where aircraft crashed in the jungle, using coordinates provided by witnesses. Sandercock would produce an enlarged map with detailed references for those areas, so bodies could be retrieved after the war for burial in the US. A map of Bougainville in the library collection is an example of her work.

“Mum was very skilled, and had an incredible eye for detail,” Fearnley says. “They recognised that talent, so they called her to the security section.”

“We had to swear that we would not reveal anything of what we saw or worked on in this section,” Sandercock wrote. “It sounded very special indeed. At last, I felt I was really going to do something constructive towards the war effort.”

Japan was beginning to retreat; Australian forces were slowly reclaiming villages in Papua New Guinea and the allied nations were fighting across Indonesia and the Philippines. Still only 19, Sandercock’s job was to map infrastructure such as airfields that needed to be rebuilt during this effort.

Next, she moved to the intelligence section, where Fearnley says she did “her most exciting work” transforming aerial photos of areas held by the Japanese into perspective and target maps. Sandercock called it “mapping in a different way”.

Perspective maps, made on rice paper, helped airmen recognise mountain, coastline or river shapes as they approached a particular target.

Target maps were printed on edible silk scarves. The target would be in the middle of the map, so airmen did not have to orientate it mid-flight. If shot down, the airmen “could eat the scarf and destroy the evidence as to why they were in a particular spot”, Sandercock wrote.

The battle of Tarakan in the Borneo campaign of 1945 started soon after Sandercock joined this section. “Australians were involved with the Americans in that amphibious landing, and what a fierce battle it turned out to be,” she wrote.

“You have probably heard of the kamikaze pilots who each flew their bomb-loaded plane into a ship to destroy it. They were prepared to die if it meant the only way to achieve that aim.”

When the war ended, “mum didn’t go out and party”, Fearnley says.

“Mum took her last map, and she rolled it up with the aerial photo. I found that when she passed away.”

Cartography suited Sandercock, who had “a great possession of pencils, pens and artistry,” that she used “in a really practical way”, says Queensland state library’s specialist librarian, India Dixon.

“Because the work she was doing was relatively covert – it is a story you don’t hear very often.”

The collection donated to the library offers an insight into women’s roles during the war.

“It was such a dynamic era for women’s ability to work” Dixon says, pointing to tram conducting and radio operations as avenues of work that “suddenly women could pursue”. But Sandercock’s role was far from typical.

“It was uncommon for Australian women to sign up with the US military forces,” Dixon says.

The presence of the US military in Australia was unprecedented, and the biggest foreign force on Australian soil during wartime.

“In Brisbane alone, there was one American serviceman for every three Queenslanders,” Dixon says. “There was this huge presence of US culture, US forces and individuals here.”

In Sandercock’s collection, “we are able to see that interaction in a small scale”.

The collection includes US army cartoon calendars, and letters from an American serviceman who had a romantic relationship with Sandercock. It also includes her wedding gown, made of fabric purchased from Myer with ration cards, and tools she used to create maps, such as wooden rulers, compasses and measurement tools with initials chipped into the side.

But what Dixon finds most interesting are “the little items”: tram and ferry ticket stubs, handwritten chemist scripts, liquid stockings and a hairnet made of human hair.

The ephemera provide a rare paper trail of Sandercock’s life.

“It creates a really rich portrait of a young woman … [and] lends a level of detail to her life and her family’s life in Brisbane during this time,” Dixon says.

“It is almost like the contents of her handbag have been preserved. It is this really beautiful stained-glass-window-tapestry of what her life was like.”

Fearnley says her mother would have been “delighted that her contribution to the war effort is being made public”.

“Partly because her individual contribution was important to her on a personal level, but also to continue community awareness of how, by pulling together as a whole, so much more can be achieved than just working as an individual.”